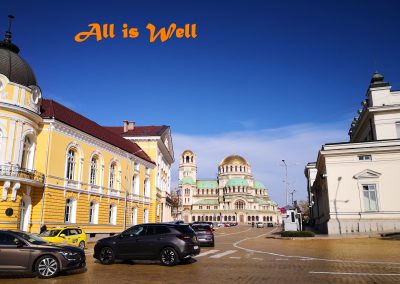

When I blogged about Accelerated Learning, proposed by a Bulgarian educator, Georgi Lozanov, on July 20, 2021 before I set foot in Bulgaria, I was only focusing on my agreement with his idea to create an immersive learning experience for the students to learn through doing and team-work, rather than researching about or around a topic. Unexpectedly, the word “accelerated” turned out to be jarringly true for me, too.

Technical University-Sofia (TU-Sofia)’s lecturing schedule has been compressed from its usual 15 weeks to 13 weeks for the first time in this semester, which has been a major change and put quite a bit of pressure on faculty and students alike. For my course, we spent the first week continuing recruiting as it was an elective course, and the last week was half a week due to the Christmas holiday, so I essentially had only 11 full weeks. For a typical TU-Sofia course, after the lecturing portion and the holiday break, there is one more month in Jan 2022 to be the exam time, when the students will have a few days to prepare for each exam, so the learning can still continue after the lecturing. For me, however, since I will leave Sofia in late Dec 2021, I have been telling the students to try to finish their projects and demonstrate them to me in person before I leave. Without that extra month in Jan, while my projects coincide with their other course assignments and midterms, the students are under a lot of pressure.

On top of the shortened semester, after the semester started in late September, we needed to move all courses online in late October given the pandemic control measures, that made things even more challenging. TU-Sofia further condensed the course schedules after moving courses online. We anticipated this possibility of going online, though, and prepared the Arduino kits for each student to borrow one, so they could still have some hands-on experiences even after our courses went online. Still, it was not as easy to do as when we were in the classroom.

That’s when the word resilience often pops in my head when I think about my Bulgarian students and colleagues.

At WCU when the four of us faculty members ran the NSF SPIRIT program, we met with the student cohort from all programs in our department and all year standings at a common time for an hour each week, when we could do interdisciplinary work (albeit still within the engineering and technology realm) and vertical integration (between different year standings). Those pedagogies were effective, measurable by quantitative metrics and qualitative interviews. That’s why I wanted to try so at TU-Sofia in this Fulbright Scholar program by offering a Project-based Learning (PBL) course. My host department at TU-Sofia (the English Language Faculty of Engineering) had been very helpful to recruit students from two programs (Industrial Engineering, and Electronics) and all four year standings into my class. Well, the logistical challenges made it hard for us to take advantage of such a class composition fully.

The students at TU-Sofia in the same year and in the same program will share a common course schedule or split into a few groups with alternating schedules. The course schedule with classroom assignment for each cohort is published as a pdf file that both faculty and students know how to interpret. I am not sure that there is much room for individual adjustment. That also means that my students won’t have much common time to fit my course into their schedules since they are from different cohorts. I polled the students on their availability from 8 am to 9 pm from Mon to Sat, and we could not fit all students in one common slot. We had to split the class in three (when in-person) or two (when online) sections, with the same content covered in all sections. Instead of having two 2-hour meeting periods each week for 15 weeks in our typical PBL course at WCU, I met with each student only once per week for 11 weeks here, so we covered only a few major topics to prepare the students for their projects. Meanwhile, the students here often need to work to support themselves or take on internships to fulfill their program requirement, so being absent is not uncommon, but they will try to catch up.

Another interesting aspect is the time restrictions on office and classroom usage. When there is a holiday, the campus buildings will be locked and none of the faculty nor students can enter. We only have our office keys but not the buildings’ keys. During this fall semester, the Bulgarian Independence Day was on Sep 22, the Revival Day or the Day of the Awakeners (teachers and cultural workers, et. al.) was on Nov 1, and the Students’ Holiday was on Dec 8. I’ve heard that on Sat they may allow entrance for half a day while Sun is fully locked, but I have never tried to enter on a weekend, Sat or not. When I had my class session ending at 8:30pm for the first time, I went back to my office to collect my stuff, and the security guard urged me to be quick and he would immediately turn off the lights after me. I had learned to be swift to leave right after my class, as understandably the security guard would want to leave by 9 pm and he could only leave after all others had left. Now given the pandemic, the students couldn’t be on campus anyway, but if/when the students are on campus, not being able to use some labs or classrooms at late hours or weekends could be hard for them to find time working on their club projects. I did see some electric mini-car on exhibit made by the students for a competition before, perhaps they did it during their regular hours. In another sense, though, we are encouraged not to work overtime, that’s a good thing for work/life balance. Well, I met quite a few faculty members who took on a second part-time job at some institutions or companies. The second job helps to supplement their income and provide an opportunity for them to practice in their professions.

Given the shortened class schedule and the limited access to a classroom, the student groups have done their best to design and finish their projects. I am very grateful for the support from the Fulbright commission and the colleagues here at TU-Sofia to get us the Touchboard kits, a new 3D printer, and the peripherals.

Beyond the aforementioned challenges, we have been constantly adapting our collaboration strategies.

- Originally we had planned to let the students from both our WCU SET programs and the TU-Sofia programs to work on a common project remotely together, but my WCU collaborator was assigned to teach other courses, and it wouldn’t be easy to fit such a project in another colleague’s course on a short notice.

- Then I thought of asking the WCU Art department’s students in another collaborator’s class to provide some comments on the design aspect of TU-Sofia’s students’ work. However, given the schedule mismatch (WCU classes end in early Dec, while our projects’ wrapping up time is in mid-Dec), this wouldn’t work out, either.

- The third plan is then to ask some American friends in Sofia to give our students some suggestions on the designs, which could finally happen. I conveyed the message between the students and the friends, and the students would be the ones to make the final decisions on their designs.

We have been trying to figure out a way to do 3D printing for student projects. This process turned out to be a series of accidental discoveries. In a big university, it is hard to know what everyone is working on, and it takes time to connect the dots.

- Originally we were not sure if there was a 3D printer lab on campus at TU-Sofia, and my WCU colleagues had offered to print and ship the parts over.

- Through online search, we found some 3D printing shops in town, which would always be a backup plan.

- When we got to know more people on campus, it led to an opportunity for us to visit the prototyping center on campus, where they would do many kinds of additive and subtractive manufacturing for small orders (up to hundreds of pieces), and it was a very useful test bed for both faculty and students to try out their ideas. There are metal printers and other types of 3D printers in those departments, but it would be not convenient for us to use their printers for our class.

- With some remaining grant, we took the plunge and bought a 3D printer. The seller in Sofia would even assemble the printer for us to pick up. It was great service.

- Later in the course, I got to know that the Industrial Engineering students would have learned Inventor or SolidWorks (CAD software for 3D modeling) from their other courses, and an Electronics student owns a 3D printer. We spent only one week’s time on this topic, and the students were encouraged to continue using whatever tools they were comfortable with.

- Not long after, we got to know a couple of colleagues who had done research on 3D printing for many years. They had customized their printer in many ways both in hardware and software so that it was not user-friendly for other people any more, but they had access to other 3D printers and they offered to help out on our emergency printing tasks if the students would have too many printing requests at once.

Although the details of our final implementation have morphed from our original expectation, things worked out in the best way possible. It has been a learning experience for us to constantly get our assumptions challenged, as many things we took for granted were not necessarily true everywhere. The very kind hospitality and strong support from many colleagues, students, and friends all around were what made our course possible.

Recent Comments